When foreigners visit Brazil, one

of the first things they tend to notice is the heavy security presence

everywhere they go. Houses and apartment buildings are hidden behind high walls and

electric fences, private guards stand at the entrances to stores and shopping

malls, and cameras everywhere remind passers-by that they are constantly being

filmed. Visitors also quickly become aware of how cautious local residents tend

to be in their daily lives, whether it involves going out on the street,

leaving doors unlocked, or stopping a car at a red light.

For those unaccustomed to this

world, it can be a difficult reality to adjust to. In many ways, it makes Brazil

feel unwelcoming and reinforces the perception that this is a society rigidly

divided along class lines, where interaction between groups is fairly limited.

It is easy to feel trapped in a bubble, moving from gated sanctuary to gated

sanctuary, unable to wander freely and securely. Whereas in the U.S. it is

common for people to spend time playing in their yards and many scoff at the

us-versus-them “Gated

Community Mentality”, in Brazil it is accepted as fact that any worthwhile

property will need a heavy layer of protection in order to be livable.

Yet, after spending more time in

this country, it becomes much easier to understand the “bunker mentality” of

many Brazilians. Simply put, these communities are very dangerous. I have heard

enough personal accounts of armed break-ins, kidnappings, and car thefts to

understand that the intense security truly is necessary for people to feel

safe. Violent crime in Brazil has long been legendary; tourists in Rio are

constantly advised to remain on guard against kidnapping, carjacking, and armed

robbery. The past few decades have seen the problem become more acute: the

national homicide rate has jumped from 11.7 murders per 100,000 people in 1980

to 26.2 in 2010, putting it on par with infamously chaotic Somalia.

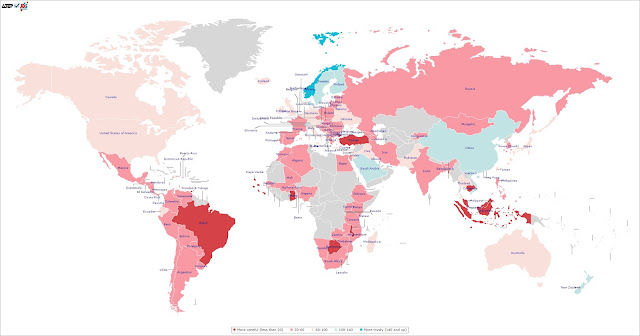

Aside from creating the need for a ubiquitous security presence, Brazil’s crime problem has an even more pernicious effect on society: the erosion of interpersonal trust. Because of the need to constantly be on guard against potential threats, Brazilians are trained instinctively to be distrustful of strangers. This effect has been studied closely through so-called international “trust surveys” where respondents are asked whether, in general, it is ok to confide in others or whether it is better to be more cautious. Brazil consistently comes out toward the bottom of these rankings, as shown by this “World Map of Interpersonal Trust”:

It should be pointed out that

Brazil is not alone in this regard. The Latin America region overall is known

for high crime rates and low levels of interpersonal trust, measured annually

in the Latinobarometro

surveys. While Brazil may be the most extreme example of this issue, the

trust deficit is also widening

in countries like Mexico that are bogged down in endless drug wars that

have led to spikes in violence. Even Chile, considered the most stable and

prosperous of Latin American nations, compares

unfavorably to the OECD countries on this important indicator.

While the importance of

interpersonal trust may seem somewhat nebulous, it should not be overlooked. Latin

America is still undergoing a period of democratic consolidation, and

institution-building is an essential priority to creating open, inclusive societies

with dynamic economies. When people do not trust each other, it becomes more

difficult to build efficient legal systems and bureaucracies and there are more

barriers to promoting economic interactions. Societies become less cohesive and

participatory and people separate themselves more and more into isolated

enclaves. Any attempts to create pluralistic democracies will be undermined if

a country is plagued by a persistent trust deficit.

When looking for factors to

explain Latin America’s crime and trust problems, many people tend to point out

inequality. Countries with high rates of inequality, such as Brazil, tend to

have high crime rates and low levels of interpersonal trust, whereas more equal

countries such as Norway and Sweden tend to have the lowest crime rates and the highest levels of trust. As the most unequal region in the world, it should

come as no surprise that Latin America has the highest trust deficit as well. Unequal

societies are a natural breeding ground for crime because they create supply

(material wealth concentrated in the hands of a few) as well as demand (poor

people with either resentment of the rich or the desire to imitate the lavish lifestyles

they witness daily).

But the other closely-related

factor that is sometimes overlooked is in many ways more direct: the presence

of “law-and-order” institutions. While inequality may sow the conditions for

crime, it is a breakdown in policing structures that makes it viable. Often,

therefore, violent crime tends to spike in periods of transition between established

orders. Recent

research has noted that Brazil’s upswing in crime came about during the

fall of the military dictatorship and the transition to democracy. A similar

phenomenon was observed during the collapse of apartheid in South Africa and,

so far, the Mubarak regime in Egypt. These examples underscore a point that

often is not recognized in discussions about crime: transitions from

dictatorship to democracy are often accompanied by waves of violence that erode

societal trust and create barriers to forming new, inclusive institutions.

Indonesia, another country that recorded low levels of interpersonal trust on

the map above, is still going through a democratic consolidation process that

began in 1998 and has seen sporadic outbreaks of violence and secessionist

movements. While traveling in China in 2008, I was struck by how safe I felt

wherever I went; the country’s highly fortified police presence, while meant

primarily to quell domestic unrest, made it easier to feel relaxed and secure.

In a chaotic transition period, it is easy to imagine how a sudden power vacuum

can lead to a surge in crime.

In Brazil, the surge in the

murder rate occurred during the transitional decades of the 1980s and 1990s,

when the nation was working to consolidate a new democratic regime. The murder rate

has dropped slightly since 2003, though it remains much higher than

pre-1980 levels:

This suggests that the worst may have passed, and that steady

improvements in policing and reductions in inequality could slowly enable the

country to overcome its violent past. It is, of course, an incredibly complex

challenge to break the cycle between low interpersonal trust, high crime rates,

and high inequality. There are no quick fixes and simple solutions. But success

stories indicate that progress is indeed possible. Much has been made of the fall in crime rates in the U.S.

and the numerous attempts to identify the key factors. Brazil’s Southeast

region has seen a similarly

stunning decline, with the homicide rate falling by 48.6% in Rio and 67.0%

in São Paulo between 2000 and 2010. (Unfortunately, this was somewhat negated

on a national level by spikes in violent crimes in the North and Northeast.) As

in the U.S., no

single analysis has emerged to clarify the underlying causes. At the very

least, the figures provide reason for optimism that Brazil can ultimately turn

the corner on this issue.

The next few decades will be a

crucial test for Brazil to address this lingering problem. It

is a shame that people here constantly have to walk around with their guard up

and feel that living in gated communities is the only way to have a house with

a yard and a social environment where people can interact openly with their

neighbors. If the nation can

finally bring violent crime under control and create an environment where

citizens feel relatively safe out on the streets and in their houses, it may

help to solidify interpersonal trust and reduce the need for omnipresent heavy

security apparatuses. For a nation that prides itself on being warm and receptive to

outsiders, that would be a truly welcome change.

No comments:

Post a Comment