One of the most important

phenomena transforming the world economy in the 21st century is the

urbanization of emerging market countries. Whereas industrialized nations in

North America, Europe and East Asia underwent a broad transition to urban life

during the 1900s, most people in the rest of the world continued to reside in

rural areas, working mostly as farmers. I have written previously about the importance

of urbanization to economic development. In essence, urbanization is the

most radical change to occur in human society since we shifted from migrant

hunters and gatherers to stationary farmers many millennia ago. It enables

economies to shift from subsistence agriculture to higher-productivity manufacturing

and service activities, which allows for more specialization and, therefore, a

more diverse array of work opportunities that leads to greater wealth creation.

The overall trend line toward urbanization is very clear, as this chart

illustrates:

This second chart also

illustrates how major emerging markets are still catching up to the West, with middle-income

countries such as Brazil already well along in the process:

How emerging markets handle this

urbanization process will go a long way toward determining the structure of the

global economy. Building efficient, productive cities that provide necessary

public services and a high quality of life will be the key to unlocking the

potential of the world’s low- and

middle-income nations.

Nowhere is the need for effective

urban planning clearer than in Latin America. The region is already the most

urbanized in the world, with 80% of residents living in cities. (This number is

expected to grow to 90% by 2050, slightly ahead of the U.S. and Europe, as the

previous graphic illustrates.) Latin America has long been famous for its

poorly-organized megacities such as Santiago, Mexico City and São Paulo:

chaotic, congested urban areas known for a high prevalence of dangerous crime,

environmental degradation, and sprawling shantytowns. Latin America experienced

its urban boom in decades when public administration was weak and local

governments were ill-equipped to deal with the influx of new residents.

Municipal planners have been forced to play catch-up ever since. Changing Latin

America’s historical path of urban development is a vital task in the region’s

quest to converge with the living standards of the West.

As the most prominent and populous

country in Latin America, it is no surprise that Brazil is home to the greatest

number of urban centers in the region. The McKinsey Global Institute recently published

a study highlighting the “Emerging 440” cities in the developing world that

are expected to generate nearly half of global growth in the 21st

century. Of the 54 Latin American cities to make the list, 27 are in Brazil. In

addition to its 25 “middleweight” cities such as Goiania, Manaus and

Porto Alegre, Brazil is also home to 2 of the world’s 27 megacities, São Paulo

and Rio de Janeiro. (Latin America has 2 other megacities, Mexico City and

Buenos Aires.) Outside of McKinsey’s “Emerging

440”, with its emphasis on large cities, Brazil is also developing many smaller

regional cities. In my state of Minas Gerais, for example, Belo Horizonte is the

main city located in the center, but there are other growing urban areas such

as Governador Valadares in the East, Montes Claros in the North, Juiz de Fora

in the South, and Uberlândia in the West. With its sizeable number of large,

medium and small cities dispersed across the country, Brazil thus has a strong

urban base to serve as the motor for the country’s economic development. The

trick moving forward will be to create effective urban administration to unlock

productivity gains and improve living standards.

Brazil’s Urban Challenges

Take a quick

visit to any of Brazil’s major cities and the scope of the country’s problems

becomes quickly evident. These urban areas tended to develop in a very chaotic

fashion, with patchy public services such as electricity, clean water, waste

collection and sewage treatment. Housing is clearly lacking, and many poorer

residents have resorted to building makeshift slums on occupied territory,

leading to the country’s infamous favela problem.

Transport infrastructure is also lacking, leading to disorderly and confusing neighborhoods

where narrow roads twist and turn without any clear overarching structure.

There is little to no effort at urban zoning, meaning that residential houses,

nightclubs, factories, stores, and other properties are all interspersed

throughout the city in no coherent order, making the organization of the city

that much more challenging.

While these

issues have always been a problem for Brazil, they have become painfully acute

in the last decade as a growing middle class upends traditional urban

structures. As befits one of the most historically unequal countries in the world,

Brazil’s cities have long been defined by the gap between the haves and

the have-nots. The country’s glaring wealth gap has often shocked foreign

visitors who have difficulty in adjusting to the jarring views of luxury

apartments located next to sprawling favelas, as in the following picture:

Yet Brazil’s

ongoing economic transformation is beginning to render such traditional depictions

obsolete. While the country remains extremely unequal, it is increasingly becoming

defined by its growing middle class, which just a few years ago became the

majority of the country’s population. The growth of this consumer class has led

to explosive demand for automobiles, housing and electricity. Brazil’s

municipal governments are now under greater pressure than ever to provide

quality roads and public transportation, build residential areas with access to

clean water, energy, and sewage, and design effective public health, education,

and policing systems. Whereas Brazil’s wealthy families have traditionally

eschewed the government to pay for their own services and its poor families

were accustomed to being ignored or mistreated, its emerging middle class has

raised expectations for what local government can and should provide for its

citizens.

One of Brazil’s

greatest challenges to improved urban planning is the inherent difficulty

involved in redesigning cities that are already highly populated. It is difficult

to design new roads, communities and public transport when that would involve

tearing down and rebuilding certain parts of urban centers. Whereas China has

prepared large urban infrastructure projects in sparsely populated cities in

expectation of future migration booms, Brazil is trying to accomplish the feat

after, not before the fact. (China’s approach is not without its own problems,

as many have criticized the country for an unsustainable building boom in ghost cities, creating a

bubble that is sure to pop.) Therefore, in addition to the basic challenge of

organizing its cities, Brazil faces the additional difficulty of having to

integrate pre-existing communities into its design.

Integrating the Favelas

Nowhere is this

challenge more apparent than in the favelas. Long the centers of urban violence

and drug trafficking, Brazil’s favelas often operate as independent states

where local authorities do not dare enter. This exacerbates crime issues and

also makes life difficult for the slum residents who are often forced to live

in fear. In order to change this situation, the Rio government has been implementing

a favela pacification project as part of its World Cup and Olympic

preparations. With help from the army, it has sent police pacification units

into 26

local favelas near the city’s famous “South Zone”, along the beaches of

Ipanema and Copacabana. The goal of the pacification units is to push out the

drug traffickers and create space for the local government to move in and

integrate the communities into the rest of the city. If successful, the

pacification policy may end up being replicated in favelas across Brazil.

So far, there

have been both positive and negative signs. Increased provision of public services

shows that the communities are indeed becoming integrated into the city. The

municipal electric utility has seen its number

of clients explode, with 160,000 new individuals connected to the grid and

delinquency rates falling from 59% to 10.6%. The government is also working to hand

out property titles to favela residents in the occupied communities, thus

validating their home ownership. Banks are beginning to install branches in the

favelas, providing access to credit, and a new

gondola in Complexo do Alemão has offered a new, innovative form of

transportation for residents of the isolated, hilltop community. Perhaps most

important of all, crime is on its way down, making the notoriously dangerous

city significantly safer.

Yet not

everything has gone smoothly. Conflicts between favela residents and police

units have led to tension in the communities, and sporadic outbreaks of

violence still occur. There are increasing worries over gentrification, as wealthier

individuals move into the community and drive up prices, breaking up

traditional social structures and forcing residents to the city’s periphery.

There have been other complaints about more direct

government bullying, as favela residents are pushed off their property to

make room for new projects for the World Cup and Olympics. The pacification

forces have also created a new problem: renegade

police militias that take over the communities and repeat the violent,

corrupt rule of their drug trafficking predecessors. Marcelo Freixo, a current

candidate for mayor from the hard-left PSOL, built his political career on

investigating and criticizing

state and local government complicity in the city’s burgeoning militia

problem and was profiled in the popular film "Elite Squad: The Enemy Within". The final drawback to the occupation policy is that, unsurprisingly, pushing

the drug traffickers out of one region has simply made them pop up in other clandestine

areas, further away from government control. Instead of solving the problem of

urban crime and the drug trade, the pacification units simply relocate it.

Despite the

drawbacks, the pacification policy seems to me to have been a major success.

The remaining problems—police corruption, gentrification, drug-related crime—are

fundamental issues of urban society that no country has been able to completely

solve. The pacification policy was not designed to end crime or inequality, but

rather to reduce it by providing the overall security cover to slowly integrate

slum communities into the rest of the city. In this respect, it is clearly

moving in the right direction. Violent crime is down, public service access is

up, and the occupied favelas no longer operate as separate

states-within-a-state. The real test of the policy will come after

the Olympics when the pacification units withdraw, to see if the integration

becomes self-sustainable. If so, one of Brazil’s urgent priorities will be

to replicate it across the country. Occupying 26 favelas is a promising start,

but it is just a drop in the bucket when one considers the hundreds of major

slum communities still under control of the traffickers. Favela integration

will be a long and difficult process.

Other Major Issues: Developing the

Periphery, Sustainability, and Innovation

Although favelas

may get all the international publicity, there are other integration problems

facing Brazil’s major cities that are perhaps more important. Chief among these

concerns is the integration of the periphery. While the country’s elite tend to

live in luxury high-rises in the city centers, the growing middle class has

been forced to look for affordable housing in less convenient areas further

away from the center. Current transportation structures are designed on a “hub-and-spoke”

model with all activity and transport flowing between the center and individual

communities along its edges. This leads to huge amounts of congestion and

inefficiency in terms of transportation. (This is a problem faced by urban

planners all over the world.) New roads and public transportation systems will

have to be designed that emphasize circular, ring-based patterns that allow for

transit to flow in different directions and enable more interaction between

communities on the periphery. To have an idea of what such design would entail,

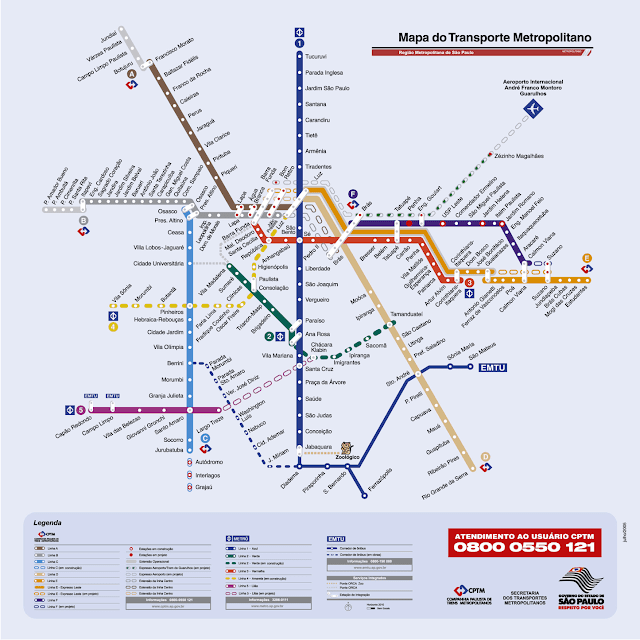

here are two contrasting pictures of the São Paulo metro (hub-and-spokes) and the Beijing metro (more circular design):

São Paulo Metro

A similar effort

will be needed to build “beltway” ring roads that allow traffic to move

circularly around the city as opposed to moving through the city center. Such

systems are standard in the U.S., Europe and East Asia. This will greatly improve

urban transit flows and reduce Brazil’s congestion problems. Once again, a comparison between the São Paulo city map and the Beijing city map is useful to understanding visually the different road structures of the two cities.

Another issue

Brazil faces is its need for sustainability, particularly better environmental

enforcement to improve urban air quality and limit pollution. I am often struck

here by the low standards for truck emissions and the thick hazes of smog. Yet

in this aspect, the country is moving in the right direction, albeit slowly. São Paulo now requires

emissions checks for vehicles, a practice that should become more widespread

and rigorous over time. More investment will need to be made, however, to

upgrade truck fleets to more modern, low-emissions vehicles. There is strong

public demand for more bike paths and metro systems, and the fact that these

topics are increasingly becoming part of the national conversation shows

Brazilians’ desire to switch to lower-polluting forms of transport. Also, as I

have obviously mentioned many times before on this blog, Brazilian cities struggle

with their waste management and low overall recycling rates. The main urban centers have also tended to neglect their rivers and inadequately treat their sewage, making waterways such as São Paulo's Tiete inhospitable and reducing opportunities for pleasant urban green space such as riverside parks. On a positive note,

the country’s reliance on hydroelectric power means that power plant emissions

remain quite clean, making air quality better than it would otherwise be.

Overall, when it comes to the sustainability of Brazilian cities, there are

both positives and negatives, and many challenges ahead. Like other countries across

the world, Brazil has much work to do to make its cities greener, more livable,

and more sustainable.

In addition to

better planning and infrastructure, Brazil also needs to embrace innovation in

its urban development process. The rising number of global cities offers

opportunities for exciting local experimentation to solve issues faced in urban

areas across the world. Rather than simply copying existing Western models of

urban planning, Brazil should embrace new technology (especially digital IT

systems), encourage individual cities to test new approaches, and promote the

replication of successful pilot projects. Brazil has a good track record in

this area. Perhaps the most famous example is Bus Rapid Transit (BRT),

a system of high-speed bus lanes and stations that was pioneered in the southern

city of Curitiba. BRT was so successful that it was eventually implemented in major

cities such as Los Angeles, Beijing and Bogotá. Brazil is now working to

install the system in 11 other major cities, including São Paulo and Rio.

Another example is the IBM

“Smarter City” command center recently installed in Rio, which serves as a

focus point for coordinating the city’s crisis response and infrastructure

systems. On a more personal note, Belo Horizonte’s inclusive waste management

system that promotes the integration of catadores has also served as a model

for similar efforts across the globe and is the reason I wound up in this city.

These examples of experimental local projects highlight Brazil’s potential for

innovative thinking and ability to pilot test new ideas in 21st

century urban development.

Municipal Elections and the World Cup: A

Country at a Crossroads

As Brazil gears

up for a new round of municipal elections this October and the World Cup in

2014, urban development has become a hot topic of discussion. The Brazilian

government portrayed its role as a host country as a chance for the nation to

embark on a wave of modernization projects to bring its cities into a new

era, making big investments to lay the foundation for major productivity gains

and sustainable development. In many ways, this could be Brazil’s biggest

chance to overcome its history of urban mismanagement and announce the country’s

emergence on the world stage. And candidates from across the political spectrum

are currently running across their cities, vying for the chance to be the

leaders to turn this dream into a reality.

Construction has

certainly been booming in preparation for the events, but progress has been

slower than many had hoped for. Officials from FIFA (the international soccer federation) have gotten into public spats with their Brazilian counterparts,

complaining about the lack of adequate preparation and repeated delays to

projects. As many projects fall behind schedule, people are beginning to worry

that the country is squandering its chances to finally overcome its urban

development issues. And in some cities, particularly Rio, there

are complaints that many projects have been poorly planned to meet the

country’s real needs, and that instead of untangling congestion problems, they

will end up as mere white elephants. While the national government may talk

about increasing investment and innovation, in practice it has done little to

reduce the nightmarish bureaucratic processes that lead inevitably to delays, cost

overruns, and uneven planning. Even among its Latin American peers, Brazil’s implementation

record remains weak. Whereas São Paulo and Mexico City started to construct

their metros at the same time, São Paulo has only 71 km of lines, whereas

Mexico City boasts more than 200 km. Improving upon this sort of weak track

record will require a major overhaul in public administration. This is not

something that can change overnight, even for an event as urgent as the World

Cup.

Over the long

run, however, Brazil’s chances still seem bright. The World Cup will result in

major upgrades to local roads and airports (as well as the favela integration

project) that will form important first steps for the country. And democratic

pressure is increasingly holding local government officials responsible for

providing results. Improving urban transport and public services is a nonstop

complaint among local Brazilians, and is the first topic to appear in nearly

all mayoral debates and television ads. Recent polling data shows that

candidates’ voter support is very directly tied to the perceived effectiveness

of the administration in office, meaning that the public is doing a relatively

good job keeping track of the government’s performance and promoting

accountability. The more that public pressure grows, the more that

business-as-usual will become an unacceptable approach for government officials.

Urban

development is never a sudden process. It is built slowly over time, developing

more effective public administration to reduce corruption, invest in

infrastructure, provide public services, integrate communities, promote

sustainability, stimulate innovation, and enhance democratic accountability.

Brazil is clearly making progress on these fronts, although major hurdles remain. It will be up to the country’s next crop of mayors to build

productive, efficient cities that enhance the country’s economic activity and

improve quality of life for its citizens. While much of the world’s focus may

be on actions by the national government, it may be local government that ends

up making the most important stimulus push of all.